In the 20s, 30s, and 40s, if I remember correctly, when the country was experiencing social and economic upheaval, Hollywood started putting out these cheesy, blockbuster, fantasy, feel-good movies along the lines of Zeigfield Follies. This period, not coincidentally, was also the birth of worldwide fascism. We seem to be here again, all of us drunk on disappointment and yearning for escape.

I don’t like to cut down the work of others, especially when it represents such an huge effort on the part of so many. This movie gave a lot of good jobs to a lot of people, with a cast that looked to be at least 45% black. I wanted to like it, but I didn’t. Hated it in fact. I wouldn’t have gone, except that my 16-year-old daughter invited me, and when your teenager asks to spend time with you, rule of thumb, drop everything and do it. I had to keep my scathing criticism to myself, because she loved it.

Let me start with the good stuff. Emma Watson did a great job, and who knew she could sing? The fact that she was able to take her role seriously and lend genuine character to this vapid role is a mark of true talent. Also, besides having a cast that 45% people of color at least (even though all the stars were white), there were a few bows to gayness. Kudos.

Now for the bad. First of all, Disney/Hollywood needs to realize that there are more than six fairytales, and we really don’t need another Cinderella, Beauty and the Beast, Snow White or Sleeping Beauty. Been there, done that five or six times.

Second, from the moment the old woman/witch appears in the first two minutes with thunderous music, a clap of lightning, and door thrown wide, I thought, “Where can they go from here?”

Don’t get me wrong, I enjoy a good, escapist fantasy, and have high tolerance for Hollywood formula films that has some inventive subscript, like the humor in Guardians of the Galaxy. Then again, maybe I’ve finally seen one too many, and am one of the few that wants to shake Hollywood off its fanatical devotion to that formula to the exclusion of all else.

Even for Hollywood, though, this movie was overblown, hyper-stylized, and vapid. Do I repeat myself? Very well, I repeat myself. The movie contains multitudes of sins in tastefulness. It was the Disney cartoon made flesh. They didn’t try for any new interpretation, nuance or depth.

The set was beautiful but so ornate that it was constantly calling attention to itself. Maybe it was just that the one-dimensional characters couldn’t stand up to the set design. That’s all the movie was, really, a vehicle for set design. To be fair, the only seats left in the theater were about three feet from the screen, so that might be why I was choking on the set.

However, it’s ironic that a movie whose message was to look beyond the surface, was all about surface.

At one point the director appeared to be trying for depth by giving the beast a backstory (or maybe that was in the Disney original; I don’t care to waste time looking it up). The poor vicious prince was wounded by the death of his mother and twisted by an evil father. I wasn’t convinced. I doubt Trump was abused, for instance. I think he’s just insane and spoiled, but we can blame the Trump phenomenon for why this movie is so popular right now.

At one point the director appeared to be trying for depth by giving the beast a backstory (or maybe that was in the Disney original; I don’t care to waste time looking it up). The poor vicious prince was wounded by the death of his mother and twisted by an evil father. I wasn’t convinced. I doubt Trump was abused, for instance. I think he’s just insane and spoiled, but we can blame the Trump phenomenon for why this movie is so popular right now.

Also, they were trying for some depth when “Chip” the boy teacup asks his mother why they were all punished for the wicked prince’s callousness. She, played by Emma Thompson, explains because, “We all sat around and watched [the abuse] and did nothing.” But they were servants. Disney seems to forget that servants have no power, and could have done nothing. Oh well, it’s fantasy, right?

Still as John Gardner famously said in The Art of Fiction, and this isn’t an exact quote, the reason we believe that the bird is talking is that when it flies to the top of the house with a nut in its mouth and opens its mouth to speak, the nut obeys the laws of reality and rolls down the roof.

I just don’t understand why anyone would spend so much money on a project like this. Oh right. Money. It made a lot, and got rave reviews, even from the New York Times, which is testament to how bad American cultural tastes are right now, and how desperate we all are for pretty escapism as we navigate our way through this nightmarish political turning point of American history. I guess it gave a lot of jobs to artists….

Watch Moonlight instead.

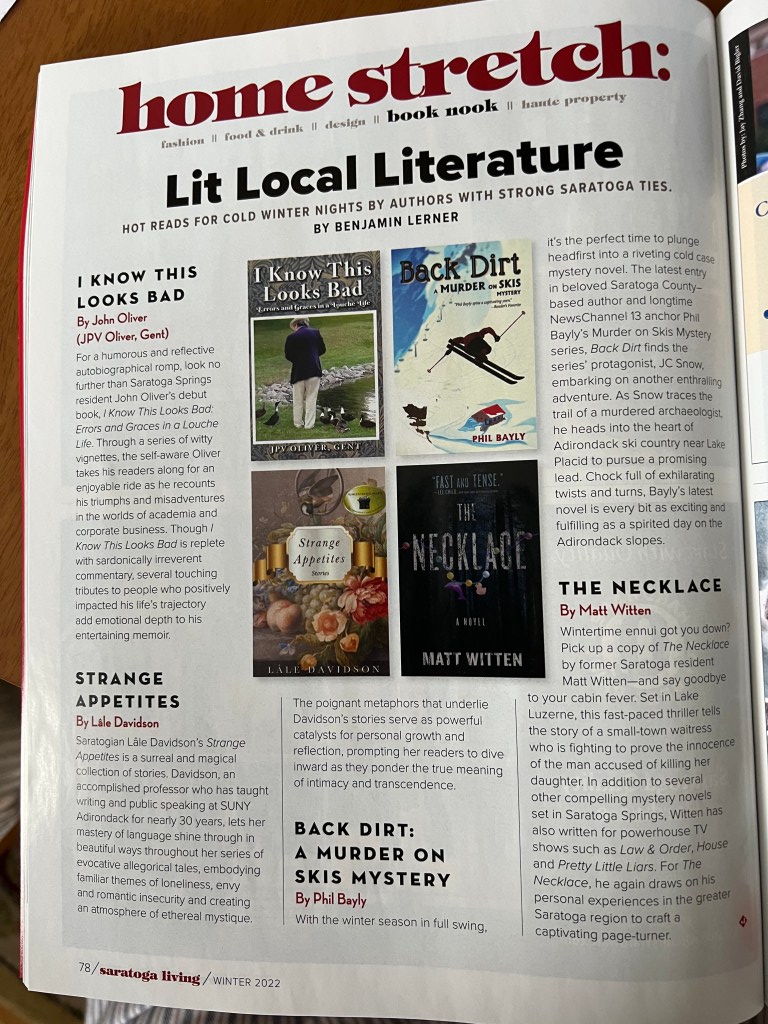

Cimarron Review

Cimarron Review When I grabbed Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude off the shelf to re-read, I didn’t realize it was the 50th anniversary. Stifling my academic urge to write a long literary analysis, I’ll just tell you a few things that struck me the second and third time through.

When I grabbed Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude off the shelf to re-read, I didn’t realize it was the 50th anniversary. Stifling my academic urge to write a long literary analysis, I’ll just tell you a few things that struck me the second and third time through.

Though there are characters in this novel, they keep repeating, as do their names, so there are many Aurelian’s and José Arcadios, and after a while they all get mixed up in your mind, underscoring the circularity of time.

Though there are characters in this novel, they keep repeating, as do their names, so there are many Aurelian’s and José Arcadios, and after a while they all get mixed up in your mind, underscoring the circularity of time.

At one point the director appeared to be trying for depth by giving the beast a backstory (or maybe that was in the Disney original; I don’t care to waste time looking it up). The poor vicious prince was wounded by the death of his mother and twisted by an evil father. I wasn’t convinced. I doubt Trump was abused, for instance. I think he’s just insane and spoiled, but we can blame the Trump phenomenon for why this movie is so popular right now.

At one point the director appeared to be trying for depth by giving the beast a backstory (or maybe that was in the Disney original; I don’t care to waste time looking it up). The poor vicious prince was wounded by the death of his mother and twisted by an evil father. I wasn’t convinced. I doubt Trump was abused, for instance. I think he’s just insane and spoiled, but we can blame the Trump phenomenon for why this movie is so popular right now.